When US President Donald Trump signed a recent executive order that would deny citizenship to the children of undocumented immigrants living in the United States, he took aim at what he suggested was a peculiarly American principle: Birthright citizenship.

“It’s ridiculous. We are the only country in the world that does this with the birthright, as you know, and it’s just absolutely ridiculous,” said the 47th president of the United States as he questioned a principle that some of his opponents say lies at the very heart of what it means to be called an American. For more than 150 years, the 14th Amendment of the Constitution has granted automatic citizenship to any person born on US soil.

As the courts moved to temporarily block his order, various media outlets pointed out that the president’s remarks were not entirely accurate. According to the Law Library of Congress, more than 30 countries across the world recognize birthright citizenship on an unrestricted basis – in which children born on their soil automatically acquire the right regardless of their parents’ immigration status.

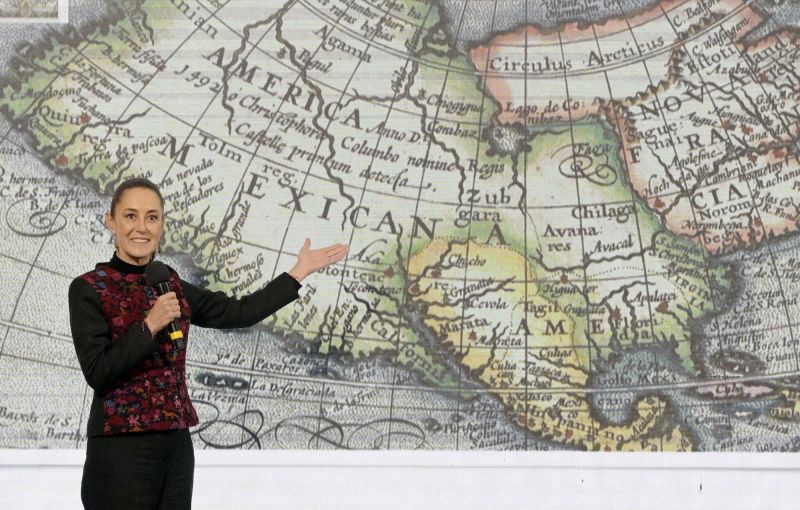

Still, presidential hyperbole aside, the data from the Law Library does seem to suggest there is something particularly American (both North and South) about the idea of unrestricted birthright citizenship, as the map below shows.

Strikingly, nearly all of those countries recognizing unrestricted birthright citizenship are in the Western Hemisphere, in North, South, and Central America.

The vast majority of countries in the rest of the world either do not recognize the jus soli (Latin for ‘right of soil’) principle on which unrestricted birthright citizenship is based or, if they do, do so only under certain circumstances – often involving the immigration status of the newborn child’s parents.

So, how did the divide come about?

Brits to blame?

In North America, the ‘right of soil’ was introduced by the British via their colonies, according to “The Evolution of Citizenship” study by Graziella Bertocchi and Chiara Strozzi.

The principle had been established in English law in the early 17th century by a ruling that anyone born in a place subject to the king of England was a “natural-born subject of England.”

When the US declared independence, the idea endured and was used – ironically for the departing Brits – to keep out foreign influence, such as in the Constitution’s requirement that the president be a “natural-born citizen” of the US.

Still, it was not until the 1820s that a movement led by Black Americans – whose citizenship was not explicitly guaranteed at the time – forced the country to think seriously about the issue, according to Martha Jones, a professor of history at Johns Hopkins University.

“They land on birthright in part because the US Constitution of 1787 requires that the president of the United States be a natural-born citizen. So, they hypothesize that if there is such a thing as a natural-born citizen, they, just like the president, must be natural-born citizens of the United States.”

The principle would be debated for decades until it was finally made law in 1868 after the Civil War, which resulted in the freedom of enslaved Black Americans, and formalized by the 14th Amendment, which states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

The economic incentive

But it wasn’t just the Brits in North America. Other European colonial powers introduced the idea in countries across Central and South America, too.

Driving the practice in many of these areas was an economic need. Populations in the Western Hemisphere were at the time much smaller than in other parts of the world that had been colonized and settlers often saw bestowing citizenship as a way to boost their labor forces.

“You had these Europeans coming and saying: ‘This land is now our land, and we want more Europeans to come here and we want them to be citizens of these new countries.’ So, it’s a mixture of colonial domination and then the idea of these settler states they want to populate,” said sociologist John Skrentny, a professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Later, just as the idea of ‘right of soil’ was turned against the Brits in North America, a similar reversal of fortunes took place in the European colonies to the south.

In Latin America, many newly formed countries that had gained independence in the 19th century saw ‘right of soil’ citizenship as a way to build national identity and thus further break from their former colonial rulers, according to the study by Bertocchi and Strozzi.

Without that principle, they reasoned, Spain could have claimed jurisdiction over people with Spanish ancestry who were born in former colonies like Argentina, said Bertocchi, a professor of economics at Universita’ di Modena e Reggio Emilia.

Right of soil to right of blood

So what about all those countries in other parts of the world that were also colonized by Europeans but today do not recognize the ‘right of soil’?

Many of them – particularly those in Asia and Africa – also turned to citizenship laws to send their former rulers a message.

However, in most cases these countries turned toward a different type of birthright citizenship that has its roots in European law: jus sanguinis (‘right of blood’), which is generally based on one’s ancestry, parentage, marriage or origins.

In some cases, this system was transplanted to Africa by European powers that practiced it, Strozzi and Bertocchi wrote in their study. But in other cases newly independent countries adopted it on their own accord to build their nations on an ethnic and cultural basis.

Doing so was a relatively easy change. As Skrentny points out, in many of these places the ‘right of soil’ had never become as ingrained as it had in the Americas, partly because their large native populations had meant the colonizers did not need to boost their workforces.

Jettisoning the ‘right of soil’ sent a message to the former colonists that “they didn’t want to hear any more of it,” said Bertocchi, while embracing the ‘right of blood’ ensured descendants of colonizers who remained in Africa would not be considered citizens.

“They all switched to jus sanguinis,” said Bertocchi. “It seems paradoxical, right? This time, to build a national identity, you needed to adopt this principle.”

So long, jus soli

There’s one final twist that helps explain why the ‘right of soil’ principle seems today to be a largely American affair.

Over the years, the colonial powers that once followed the ‘right of soil’ have since moved either to abolish or restrict its use, much like some of their former colonies.

In the UK, it was scrapped by the British Nationality Act of the 1980s, which put in place several conditions to qualify for British citizenship – including some that relate to parentage, as in jus sanguinis.

Experts say the driving force for those changes – in Britain and elsewhere in Europe – was the concern that migrants could take advantage of the system by entering the country with the intent of giving birth to a child with automatic citizenship. In other words, the same concern being voiced by many of Trump’s supporters in today’s United States.